Scalability of data processing

How can we make distributed computing more resilient, remove bottlenecks, and improve scalability?

We can often address these questions at the architectural design level, in which we plan the structure of our system and the high-level interactions between system components.

This post will focus on improving the resilience and scalability of communication between system components, and discuss incrementally more powerful models and their advantages and disadvantages.

The content for this post was compiled from a selection of notes from a guest lecture on “dealing with message backlogs”. The talk was given by Stuart Ritchie from Arista Networks on March 29, 2017, for UBC’s undergraduate distributed systems class.

Diagrams were created using Evolus Pencil V3.

Direct process-to-process communication

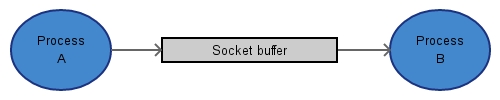

A) Simple single socket model

The traditional model of process communication is in which one process makes a direct connection to another process and transmits messages through a socket buffer.

This strategy is simple and easy to implement, but has a few design flaws that limit its throughput.

-

Data processing rates are limited by the performance of Process B.

No matter how efficient A is, if B takes longer to process data, then data will flow through the system at the slower rate. This effect compounds when we have a chain of processes, each passing its result as input to the next process, as the slowest process dictates the rate of the system.

-

Messages from A will overflow the socket buffer if B cannot process them fast enough.

The socket buffer has a finite, small capacity. While B is busy, messages from A will accumulate in the socket buffer until it has to either drop messages or block A from pushing further messages in, which may cause undesirable behaviour in A.

We could modify A to wait for B to pick up a message before sending a subsequent message. However, we would rather make use of A’s processing power than let it sit idle. Pausing A will also block any processes behind it.

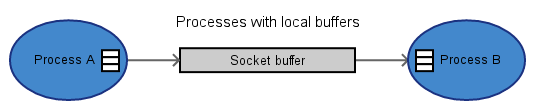

B) Single socket model with local buffers

Maintaining local buffers in A and B allows A to continue working until the buffers have filled, but only buys us time in the case that B is less efficient than A.

If we receive a large, continuous stream of data and B processes data slower than A, then we will eventually hit the same message overflow issue.

We can replace fixed-size local buffers with expandable hash tables, which defers message overflow until one or both processes run out of memory. Process memory is finite, so this will also hit a wall as we increase the frequency of messages.

General notes for the single socket model

The single socket model struggles with rate limits when downstream processes are slower than those upstream, regardless of whether local buffers are used.

Buffering doesn’t address the root issues that are causing our bottleneck, and only buys time for slow processes to catch up on message backlogs when high input frequencies are rare and intermittent.

Additionally, these models tightly couple data to particular processes, making it difficult to recover if one process fails and takes with it any data it may have accumulated.

We need to consider more powerful models in order to scale up our system to handle sustained high message rates.

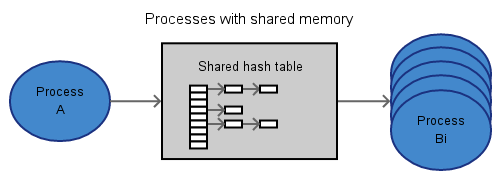

Communicating through shared memory

Suppose we introduce a form of shared memory between A and B. Then, any number of processes can pick up messages that have been processed by A.

This model has the advantage of being fully decentralized in how intermediate messages from A are processed, which improves our fault tolerance if one of the B processes fails.

No local message buffers are needed for the A or B processes, so if one process fails, at most one message is lost and the other processes can continue working on the remaining messages. If every message is important, we may be able to add complexity to our system to make transactions atomic and avoid removing records of messages until they have been fully processed by a given stage.

The model is transparent to the implementation of the shared memory, which can be a single instance of a queue or any other collection, distributed between machines, or backed up as necessary.

A significant benefit of this model is that we’ve decoupled the two stages of data processing, so that every process can run at their natural speed without accumulating a backlog if one process stalls.

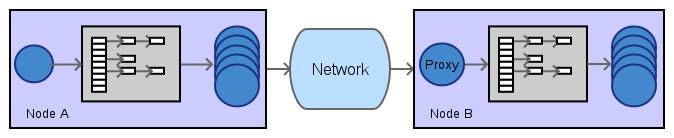

Communicating between machines

The shared memory model works well for a single machine with multiple data processing stages.

What if we have too much work for a single machine to take on, or we want to chain machines together to spread processing stages across a network?

We can use our earlier model to implement nodes that each have a self-contained structure.

We can use the input process of a downstream node as a lightweight proxy that accepts and passes messages to its node’s shared memory. This reduces the risk of it acting as a bottleneck, while allowing us to distribute work efficiently.

We retain the scalability and fault tolerance of individual nodes, which are able to fully utilize their output processes. Multiple nodes can be set up to pick up work to ensure healthy throughput for varying frequencies of input messages.

We can extend and modify these models to produce resilient and scalable systems.

Key ideas

- Failure tolerance and scalability requirements often call for changes to architecture design.

- Single process-to-process communications have limited scalability and can lead to failures when one slow process leads to an exploding message backlog.

- Replacing buffers with shared memory decouples data from processes and enables work sharing.

- Decentralization of work can help to eliminate bottlenecks and improve failure tolerance.

Helpful resources:

- Course notes from UBC CPSC 416: Distributed Systems: http://www.cs.ubc.ca/~bestchai/teaching/cs416_2016w2/index.html